On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Africa Alive Festival in 2018, we had invited to an all-day „Human Rights Day“ with African and European activists at the Haus am Dom in Frankfurt on the Main under the title „Human rights for all, without borders“. The journalist Emanuel Matondo was also a guest. Born in Angola, he has lived in Germany for decades. He campaigns for human rights work, against racism and for the rights of people of African origin in Germany and Europe. „For 400 years now this racism has been going on“ – for Matondo it is important, as he says in a paper, „to raise our voice audibly against continuing crimes of racial discrimination and hatred“. The frame of reference for this, he is convinced, could be provided by the documents of the World Conference against Raciscm, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, which took place in the South African city of Durban in 2011, and the UN International Decade of People of African Descent from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2024, if they were discussed more widely. He said it was time for the eight slave-holding nations, including Germany, to finally come to terms with their colonial history, overcome defensive patterns and create a new culture of remembrance.

We spoke with him in Frankfurt about the legacy of German colonialism, the question of compensation for countries that suffered under slavery, the recognition of guilt and the power of music of African origin, which he describes as La Magia del Ritmo Negro.

Cornelia Wilß: Around here the argument is often raised, that Germany, in comparison to other countries, had not been a slaveholder state. In fact, the German colonial empire included parts of the actual states Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Namibia, Cameroon, Gabon, Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Chad, Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, New Guinea and numerous West Pacific and Micronesian islands, and in competition with other colonial countries for exploiting resources, Germany pursued active and aggressive colonial policies in the so called „Schutzgebiete“ (protectorates). Mr. Matondo, what do you tell people who belittle Germany’s colonial history?

Emanuel Matondo: I think it is just a very common position which is based on ignorance. There are some people in Germany who insist, however, that German colonialists had nothing do to with slavery, since Germany only at the end of the 19th century became a colonial power, but this is completely wrong. If we focus our attention on German elites for example, we get a totally different image. Already in early 17th century, the German banking and merchant families Fugger and Welser from Augsburg financed the Portuguese slave trade. The Welser family purchased shares of slave plantations in present Venezuela. We know nowadays that Frederick William, the Grosse Kurfuerst, in 1682 founded the Brandenburg African Company (BAC) in Berlin. By order of Frederick William, the Prussian nobleman Otto Friedrich von der Groeben should find a base for the expansion and organisation of the slave trade. Under these circumstances Fort Gross Fredricksburg on the coast of today’s Ghana came into existence. The fort, from 1683 till 1717, served to the BAC as transshipment point for the slave trade. Concerning the harm, especially caused by Portuguese slave traders, against people in Africa, there exists plenty of documentation on their atrocities committed in the former Kingdom of Kongo (ed.: in present parts, of Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Gabon). People in these countries still today suffer from the disastrous impacts. Slavery and colonialism have traumatized these peoples.

COLONIAL INJUSTICE AND COMPENSATION

Very few people know that the Grosse Kurfuerst ordered to build a second base in the Caribbean, on the island St. Thomas, which in that time was under Danish rule. Some estimates reckon that from the ten to twelve millions of people traded as slaves between 1519 and 1867, about 80 percent came to the plantations and mine sites situated on the West Indies, Brazil and the southern states of the later USA, and there had to do force labor. Other slaves however, and nearly nobody is aware of this, ended up on the territory of Imperial Germany where their work force was exploited. Even after the abolition of slavery, often the former slaves and People of Color were allowed to do only certain low-level jobs. At that time the everyday life of these people from Africa and later of their descendants was dominated by racism, discrimination and humiliation, which is documented in their petitions towards politicians in these past times. The racial hatred against people of African descent reached its peak, when African people of both sexes were exhibited like exotic animals, in the zoological gardens in Europe and in Northern America, for example also in Berlin’s Zoologischer Garten. In addition, this act of contempt for humanity was boasted everywhere as “the most famous world exhibition”. Black people from Africa were downgraded to „animals“, and later black people even were labeled “no humans”. We need to talk about all these things by deconstructing Europe‘s writing of history and by retelling theses narratives completely new.

The issue of reappraisal of colonial injustice always rises the issue of compensation. What do you think that should be done?

The Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) claims the governments of Great Britain, Spain, France, Portugal and the Netherlands for appropriate reparations because of Native Genocide and the Enslavement of Africans. CARICOM in 2014 adopted a Plan for a Caribbean Reparatory Justice Program (CRJP), that claims a “comprehensive, complete and formal compensation“ for these former slave colonies. The committee tasked with supervising the work of the so called CARICOM Reparation Commission is built up by Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Haiti, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Surinam, as well as by the respective chairpersons of the national Reparations Commissions and by one representative from the University of the West Indies. But in Africa you hardly gain a hearing for a claim for reparations.

Why?

Neither in official and academic circles nor in civil societies or in the population, the issue of reparations is being discussed. One single exception was the first Pan-African Conference on reparations for the enslavement, the colonization and the African neo-colonization, headed by the Nigerian politician Moshood Abiola, which took place from 27th to 29th of April 1993 in Abuja (Nigeria); this Conference got support from the Group of Eminent Persons (GEP) and from the Reparations Commission of the Organization of African Unity.

The Abuja Proclamation

A declaration of the first Abuja Pan-African Conference on Reparations For African Enslavement, Colonization And Neo-Colonization, sponsored by The Organization Of African Unity and its Reparations Commission April 27-29, 1993, Abuja, Nigeria:

Calls upon the international community to recognize that there is a unique and unprecedented moral debt owed to the African peoples which has Yet to be paid – the debt of compensation to the Africans as the most humiliated and exploited people of the last four centuries of modern history […]

Convinced that the issue of reparations is an important question requiring the united action of Africa and its Diaspora and worthy of the active support of the rest of the international community. Fully persuaded that the damage sustained by the African peoples is not a „thing of the past‘ but is Painfully manifest in the damaged lives of contemporary Africans from Harlem to Harare, in the damaged economies of the Black World from Guinea to Guyana, from Somalia to Surinam. […]

Calls upon the countries largely characterized as profiteers from the slave trade to support proper and reasonable representation of African peoples in the Political and economic areas of the highest decision-making bodies.

Moshood Abiola had won the 1993 presidential elections in democratically free elections and as a free thinker he really wanted to push through the demand for reparation payments. This was not based on any official act of the Nigerian government, but the demand of 777 trillion US dollars was on the table. Europe, the USA and also the Arab countries that had participated in the slave trade were to pay this compensation. But the presidential election was annulled, Abiola ended up in prison and died under mysterious circumstances.

On which base this amount was calculated? Which reactions did arise?

The African World Reparations and Repatriation Truth Commission in late summer 1999 for the first time spelled out a precise amount for the reparations to claim. No matter one considers these figures as silly or not, at least they provide an evidence for the atrocity of the committed crime we are talking about. But persons with such claims like Abiola did not make new friends in Western countries. It is rumored that this is the reason why Abiola got eliminated. Something nearly similar occurred, when Freundel Stuart, the former Prime Minister of Barbados announced to make a claim, in this case directed towards Great Britain, since it is absolutely proven that the British Empire owes a lot of its richness to slavery. The Prime Minister of Barbados however was put under such pressure, also in economic terms, one could or might consider an intimidation. Also concerning this topic Great Britain denies to acknowledge its debt and to do penance.

To do penance? The term penance is shaped by religion. Is it a question of acknowledging a guilt?

Exactly this is the clue: the acknowledgement of guilt. That Europe and Australia, South Africa and many Latin American countries like Brazil and Argentina, and Canada, and of course the USA, have to pronounce a confession of debt is overdue. They pretend this had been a single historical offence that once upon a time had happened, but it’s about much more.

While travelling, I exchanged views with people in Latin America, I used to interact with people in the USA, in Asia and so on. Information about crimes committed by colonialism simply is withheld by official parts. Let me give you an example!

The Jesuits were engaged in slave trade. They preferred slaves from the Kongo-Angola region, as these were considered to be especially strong and sturdy. Moreover, the slaves from there brought along a whole range of skills, which were necessary to exploit the resources in America, for example in terms of agriculture, animal husbandry and fishing, but especially in metal mining and manufacturing and so on. Hence these slaves originally came from our countries located in the Congo Basin, in fact from “my” Kingdom of Kongo. During my investigations I received the hint to analyze documents of library archives in Cartagena de Indias in Colombia and in Mexico. I was surprised! Some cathedrals constructed in Latin America were built with slave labor. But, who were the slave holders? Among all others, the Jesuits. The Jesuits even had their own trading posts in present Angola and in the former Kingdom of Kongo. These clergymen gave the order to chase and to kidnap people, and in cooperation with Portuguese slave traders, as „encomenderos de negros“, they deported the captives towards America. Especially to Mexico, Ecuador, Argentina and to Middle and South America. But also towards the USA. This history of the Jesuits as slave traders or brutal slave owners could be the subject of multi-volume horror books.

Let me add another point: Some of still persisting conflicts in Africa have their origins in the past, when the important European slave trader nations provoked destabilizing wars on the African continent, in order to facilitate the kidnapping and filibustering of Africans for their shipment towards America. Neither Africa nor the Caribbean never recovered from this dark chapter of their history. One should not simply dismiss the criticism of the role of capitalism as an „architect of racism“ and a driving force of enslavement as „radicalism“ of some wannabe do-gooders. Instead we must insist on an honest dialogue on this darker past of our common history. This is the only way to heal the wounds caused by that barbarism.

THE SUPPRESSED NARRATIONS OF RESISTANCE

Where are we standing today? Do you see a direct connection between colonialism and racism?

I think that from the times of slavery till now, a culture of dominance has persisted. After the abolition of slave trade, the “Herrenrasse” (“master race”) which we nowadays term as “White Supremacy”, invented racism in order to actually practice the pre-eminence of rising themselves above other people. The European culture and newly developed “neo-European” cultures were depicted as high-level and “more developed”, whereas African cultures and cultures of American natives were discredited as “primitive” and “underdeveloped”. This racism has persisted, because myths as well as prejudices and stereotypes were passed on.

We all know that History has not been written from the viewpoints of the others, but from the perspectives of persons who hereby cemented their supremacy. Many people still think of Black people as lazy people. But these people are not aware that enslaved people from Africa had slowed down the pace of work as an act of resistance. During slavery, many Black Africans did not resign to their fate, but, beside rebellions and revolts they also choose forms of non-violent resistance we know by the term of „Cimarronaje“, in order to evade the unjust and exploitative colonial system, they created their own free areas, sometimes in hidden places and remote locations. The slaves, by showing this behavior, caused huge economic harm, which is a narrative of resistance that in most history books is probably oppressed. Slave holders and slave traders, as I mentioned before, hence developed the stereotype that slave people, people from Africa are lazy people. Still today this mere racial stereotype dating from darker times of slavery is labeled on people of African descent, and this a ubiquitous phenomenon. Especially many Human Resources managers keep this stereotype and probably running like a bad film in their heads when, during application procedures for staffing, they finally decide against the recruitment of people of African descent, often even without any plausible explanation. At least this is my opinion.

LA MAGIA DEL RITMO NEGRO

During the last years you focused on Africa’s cultural heritage in music?

At this very moment I am working on a book with a focus on music especially about La Magia del Ritmo Negro. We need more clarification of facts. In one chapter I try to explain for example how pop culture developed, and I research the origins of reggae, rumba or milonga etc. Or just think of Rock and roll music. Rock and roll draws a lot of its origins from African cultural heritage. And jazz music: that is Black Music! The sound of Blues for example has many similarities with melodies from my region and from some other regions in West Africa. Or think of the Brass Band March, which reminds our music at funeral ceremonies. One of the most famous songs worldwide, La Bamba, is a Mexican popular song which originally came up in 1683, in Veracruz, by dockworkers on a strike, that’s to say slaves from the Kingdom of Kongo. This is a really amazing story dating back to the 17th century. Now La Bamba nearly is regarded as Mexican national anthem, the song even got as far as Hollywood and gave a movie its title. La Bamba worldwide fills people with enthusiasm. Reggae had its origins partly in the Kongo-Angola region, as well as in West and in East Africa. Especially my language, Kikongo, has contributed a lot to the first compositions. A US-American historian came to the conclusion, that our culture and our musical legacy made an important contribution to the world cultural heritage.

How can this awareness be pushed on? The International Decade for People of African Descent declared by the United Nations is a symbolic act. Which tangible actions should be done?

One should start with recognition. With the recognition of our contribution to the culture of the world, with the recognition of the fact that it had been people from Africa who participated in building up America, with their knowledge and with their skills. England, thanks to our contribution, became the rich and industrial country we know today. I mentioned this before. Just take Europe or the USA or Brazil or entire Middle and South America. Everywhere. 80 percent of the slaves kidnapped and deported to Mexico had their origins in my region, the Kongo-Angola region. They exerted influence on the cultures and arts in the countries they were deported to. Pure cultures do not exist. The assumption of the existence of a pure Western culture is a presumption. There is no Western culture. That is the biggest lie. Europe’s culture is Judeo-Christian and it is also shaped by cultures from countries we label Orient. Cultures always got mixed. Look at the American culture. In Alabama, in New Orleans. When I listened to music in such places, I sometime thought I was standing in the middle of my mother’s village, hence I recognized the sounds of the music.

I talked to people from Cartagena de Indias, and they said: ”Bullerengue colombiano, but that’s your music, isn’t! Come with us, you’ll meet your people.” I talked to people in Argentina, I’ve received so many invitations, Cornelia, from Ecuador, from Argentina, from Córdoba, from Buenos Aires. A scientist from Buenos Aires during the peak of the pandemic in 2020 wrote: “Hi, just come to Argentina.”

MY IDENTITY/WORLD IDENTITY

What is the significance of the concept of identity? Is it helpful to talk about African identity or about Black identity? At present, there is much discussion and controversy about politics of identity.

Well, I do identify myself as a Black Person. For sure! But this person is not any more like his fore-forefathers in the mighty Kingdom of Kongo in Central Africa, which extended over vast parts of present Northern Angola. With the arrival of the Portuguese also came the Dominicans, Capuchins and Jesuits, these started their missionary work and my ancestors were forced to get christened. The „primitive“ people in the new African colonies had to be converted by the use of swords. That forever changed our identity. I do confess my African heritage, but I am not any more the Matondo like the Matondo my ancestor once had been. Slavery and colonialism have caused much destruction in our regions, and in ourselves. This is why I do not have an African name. The once baptized people had to give up their original names and to adopt European names. That was the law, and it is still working. There is nothing left from the African proper names, for example in Angola. In my family things were different. We did not want to give up our names completely and we kept „Matondo”.

Who am I? I have been living in Germany for a long time, my children were born in Germany. They know about the African continent mostly from the telling of their parents. I try to talk with them about the fact that they do carry an African legacy, but their place of socialization is here in Germany.

Talking about identity is complicated. I do not conceive identity as a geographic denomination that says where one is coming from, but as a manner of how one is thinking. This is why I prefer talking of world identity, because in biographies the different cultural experiences always get newly mingled.

In many regions I may meet people who have blond hair and blue eyes, but from the biological point of view they are people of African descent. We must stop that nonsense! Only by recognizing this fact, that there is no such thing as a pure culture we will be able to get people of African descent out of invisibility. Racism starts with the invisibility and with the denial of our history. We have to change that. That is also the right of our children.

This interview was given in January 2021

Translation: Stefanie Karg

Biography

Emanuel Matondo has lived in Germany since the early 1990s. In 1998, he co-founded the Angolan Anti-Militarism Initiative for Human Rights (IAADH) where his responsibilities include research and public relations, lobbying, advocacy and actions to promote peace. He also led advocacy work aimed at achieving a peaceful resolution of the Angolan civil war with the Belgian government and EU Presidency, the European Commission and the Swiss government. While involved in these activities, he acted as a policy adviser on peace issues to the leaders of Angola’s major churches, as member of the ecumenical team behind the internal mediation between both warring parties between 2001 and 2002 (to promote an immediate cease-fire as well as a peaceful and inclusive conflict resolution). From 2002 to 2005, he was a Council member of the London-based organisation War Resisters‘ International (WRI). For several years, he also served as spokesman of Dritte Welt JournalistInnen Netz (Third World Journalists‘ Network), as well as being actively involved in the organising committee of the Deutscher Evangelischer Kirchentag (German Protestant Church Convention) contributing e.g. to the Africa Forum) and the First Ecumenical Convention which took place in Berlin in 2003. Emanuel is foreign correspondent for the independent private Angolan weekly Folha 8. From 2011 to 2018, he has also worked as an editor for afrika süd, a German magazine about Southern Africa. Since the end 2012, he has acted as consultant to the recently established „University of Peace in Africa/Université de Paix – Afrique“ (UPAIX) in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, where, in 2013, he gave a number of special seminars on „Disarmament, Arms Control and Mechanisms to Counter the Proliferation of Small Arms in the Great Lakes Region“. He also acts as a consultant to several other international organisations and institutions. Emanuel’s extensive list of publications deals in particular with the issues of human rights, refugees and migrants, arms exports, civilian peacebuilding, mining and social rights as well as corruption. He is an expert on the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review (known as the „UPR“ mechanism) and advises NGOs/institutions/groups on it.

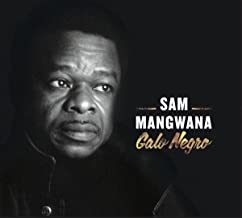

Maestro Sam Mangwana – "El Diablo del Ritmo"

Emanuel Matondo is now working on a book about the lifetime achievement of the world-famous musician, singer and composer Sam Mangwana, known as the „Prince of Congolese Rumba“. Talking in March about this project, Matondo is developing the book’s concept as well as formatting 200 lyrics out of a selection of more than 400 published songs. The book shall be published next year. In 2022 the artist Sam Mangwana will celebrate exactly sixty years of a long and intensive career as musician. The book is dedicated to a „living legend“, says Matondo, who brought the music genre „Congolese Rumba“ not only to Panafrican fame but also to international reputation. Descending from Angolan parents living in the Northwestern province Uíge, Sam Mangwana was born in Léopoldville (present Kinshasa) in 1945, the capital of present Democratic Republic of the Congo.

He composed and sung songs in nearly every important African language, in about 17 languages like Lingala, Kikongo, Swahili, Duala, Bambara. In addition, he sings and composes songs in French, Spanish, English und Portuguese. „The timing of the publication of the book is perfect, with Sam celebrating together with us the successful moments of his life as musician.“ His book is a beginning, remarks Matondo, „hence our plan is to publish as a cultural heritage for future generations, the scores of his entire oeuvre which filled our lives with music, with great melodies as well as with the sound of happiness. I hope we will succeed in this project and we will find good partnerships to realize this common project.“