Hind Meddeb was a journalist and worked for French television, then switched disciplines; she has been making successful documentaries for over ten years now.

Hind Meddeb, who was born in Paris in 1978, became well-known with two long evening-length documentaries that observes the Arab Spring (2010 to 2012) from the perspective of view of the youth rebelling against the strictly controlled patriarchy. In the role of chronicler, Hind Meddeb provides intimate insights from the inside view of the events in Cairo, Tunis and later in Khartoum. In 2020, she presented her film PARIS STALINGRAD (youtube.com/watch?v=tRSO8DMRrV4) in Frankfurt on the Main as part of the Africa Alive Festival – in hauntingly moving images, she tells of the everyday struggle for survival of young refugees from Afghanistan, Syria and Sudan in Paris.

Text: Cornelia Wilß

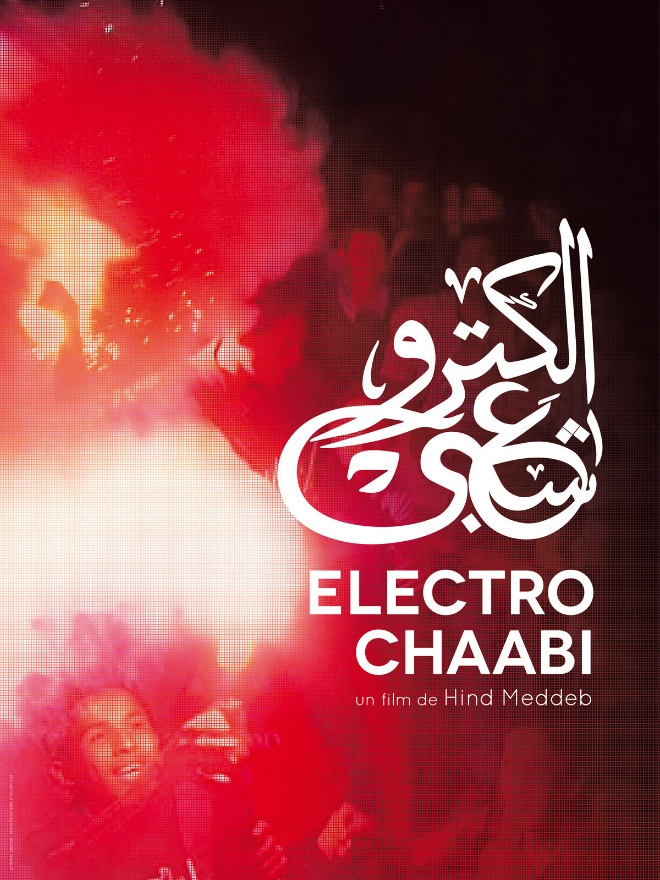

ELECTRO CHAABI and TUNESIA CLASH

The documentaries ELECTRO CHAABI and TUNESIA CLASH take the perspective of view of the revolting youth against the encrusted old and create moving moments of awakening and liberation, of hope and disappointment. Even if the assessment of the political success of the Arab Spring today, ten years later, is disillusioning, the protests have been a historical breaking point to opening up perspectives for the future. And Hind Meddeb keeps this overwhelming spirit as a political promise for a utopia that can no longer be suppressed.

The filmmaker travelled to the heart of the uprisings in Cairo, Tunisia for ELECTRO CHAABI and TUNESIA CLASH and later for OUR VOICES AS ONLY WEAPONS to the revolutionary sit-in in Khartoum. She has been accompanying people with her camera and gives the close-ups of a rebellion mainly driven by the youth. New hard beats were fascinating people; music becomes a revolutionary act of resistance – as in the 2010s in so many African countries. The filmmaker benefits from the fact that she speaks Arabic, which makes the interaction easier, she says. Hind Meddeb directs from a discreet attitude of closeness and empathy and trusts in the moment of realisation through the encounter, a smouldering spark that jumps over to the viewers.

While Egypt is best known as the home of classical Arabic music from Om Kolthoum to Abd el Halim Hafez, a new style of music has emerged in Cairo’s suburbs and poor neighbourhoods over the past: ELECTRO CHAABI. However, in a country like Egypt, where half of the population is under 25 years of age, and in a time of huge social transformation, mahraganat has become a cultural phenomenon. Based on popular music played at weddings and other street festivals, it mixes Arabic rhythms, electro and hip-hop elements with lyrics that are rapped and danced in the street. The film echoes this wave of enthusiasm. Artists like Sadat, Oka & Ortega, Weza, Fig, Chipsy and Amra Haha …. Hind Meddeb films the idols of the youth on their way to revolutionize music in Egypt and overcome social taboos.

„Emancipation of the body and unspoken words, much more than a simple musical phenomenon, electro chaabi is a salutary discharge for a youth haunted by the shackles that the Egyptian society imposes. In a conservative and religious society where bodies are restrained and where the sexual life is constantly controlled, the dance frees repressed energies. Life is constantly contradictory in its desire for freedom, the need to let off stream. While certain subjects are carefully avoided, electro chaabi relieves repressed words. The lyrics, sung back by the crowd would shock anyone stuck in the thought that Egypt is a strict conservative, religious country.„

One of the first hits of electro chaabi was the “Haram Life” song:

Haram Life

I’ve taken the road of vice out of vice

To forget my open suffering

I thought I was eternal

Time passes too fast

The days go by and pull me onward

I’ve never fasted

I’ve never prayed

I could have but I haven’t done the pilgrimage to Mecca

Even when I had plenty of money

I haven’t done any charity

Impossible to tread the right path

But it doesn’t stop me being happy

My reason has gone up in smoke

My heart is empty, I’ve lost faith

Is there still time to find the right path

In this documentary, director Hind Meddeb travels across Tunisia, from slums to deserts, to capture the pulse of Tunisian youth that might be liberated — but are not yet free from worry.

She met charismatic rappers Phenix, Weld el 15, Emino, Madou and Klay Bbj g, believing that after the fall of the regime in 2011, they now have the right to denounce the new government and the corrupt, reform-resistant system, as well as the omnipresent shadow of extremists. „This new generation of activists, followed by millions on social media, is looking for new forms of protest. For them, the revolution was not just a historical event; it is a daily struggle. Far from being based on political parties, the Tunisian revolution came from below: First and foremost, it was young people from the working class who took to the streets. At the heart of the movement were the rappers. They were around twenty years of age, came from deprived suburbs and had good reasons to make revolutionary demands.“

Oh yeah? We’ve made a great revolution?

Give me a match so I can burn the government’s script

The prisons are full of innocent people

At the next elections, I’ll vote for my butcher

The government is sucking our blood

The people in charge are getting fat […]

Insulting the system is my livelihood

Our rap is more listened to than your president

Meddeb knows Tunisia very well. Her mother is Moroccan-Algerian, her father Tunisian (the famous writer Abdelwahab Meddeb.) She speaks her parents‘ Tunisian and Moroccan dialectical Arabic and started working in Tunisia at the time of the revolution: „Before, we couldn’t do anything! I quickly became interested in the political role of music and rap in particular, especially with the rapper El Général, who first came out with his song Raïs Lebled in January 2012.“

PARIS STALINGRAD

In Frankfurt on the Main, Hind Meddeb presented her film PARIS STALINGRAD at the end of January 2020. The documentary had its premiere at the Toronto Film Festival in 2019. It is a film about violence by the state against harmless people, a process of dehumanisation and poetic resistance as an alternative.

Together with co-producer Thim Naccache, Meddeb documented the living conditions of refugees in Paris, her hometown, between 2016 and 2018. The darker sides of the glamorous city known for fashion, art and literature are unknown to the French public at large, says the filmmaker, who does not gloss over anything in her film. In France, her film had not been shown in cinemas or on television until then, she says in 2020, but now, she writes to me in May 2021, her film is starting in French cinemas from 26 May.

At the time, Hind Meddeb lived in the immediate neighbourhood of the „Stalingrad“ metro station near the Canal Saint-Martin. She filmed at the site where refugees had set up a camp that was regularly demolished by the authorities. Her film shows people trying to survive between police raids, arrests and unsuccessful attempts to get papers for a secure residence status from the immigration authorities. From the perspective of young unaccompanied refugees, PARIS STALINGRAD delivers a harsh critique of the conditions and cold-heartedness of the French state. For her, Hind Meddeb it is also personally important to show this dark side of Paris, the international metropolis that is proud of its revolutionary heritage and has raised the universalism of liberty, equality and fraternity to the pantheon in human rights issues. „I also come from a colonised country. My father was Tunisian, my mother was half Moroccan, half Algerian. My parents came because of their ideas and their belief that they could have rights and freedoms here that they didn’t have in their own countries.“ What a mistake!

In the beginning, she went to the refugees, young unaccompanied refugees from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Syria and Sudan, because she wanted to help people with translations and applications, she says.

She shares Arabic as a common language with many refugees. In France, she says, the authorities expected documents to be filled out exclusively in French. „I think this is where racism starts.“ She continues: „Little by little, I was able to build up a certain trust with people. They came to our house. We then also showed solidarity with other people and made a lot of noise, wrote protest letters to the mayor, went to the press. But the situation of the people got worse and worse, there were suicides … people were expelled from the area around ‚Stalingrad‘, now live somewhere where they remain invisible and don’t disturb the self-image of Parisians.“

Getting papers in France is like a lottery, she says: „People who come from the same region for the same reasons (as was the case with Souleymane and some of his friends) are treated differently. One gets the papers he longed for, the other doesn’t. It is not that the administration does not take their stories into account. It’s more that it’s handled arbitrarily, sometimes the reasons given for fleeing are accepted as grounds for asylum, sometimes they are rejected and the reasons for rejection are not always logical.“

Meddeb allows the viewer to participate in her search for a narrative that moves in the space between factual reality and the search for truthfulness. In PARIS STALINGRAD, Souleymane embodies the young man from Darfur who has fled and has to sleep on the street. But Souleymane is also the poet who writes poems where he finds consolation. And finally, she says frankly, Souleymane has become like a „brother“ to her, whose life she continues to observe.

Hind and Souleymane spent long afternoons by the side of the Canal Saint-Martin, meeting frequently at the Sudanese restaurant where his whole community goes for lunch. „Then he would read me the poems and I found that so beautiful.“ In Souleymanes‘ film, his off-screen poems create moments of pause. „Whenever others denied him his humanity, whenever he faced torture, slavery or abuse, whenever he had nowhere else to turn, Souleymane found comfort in the one thing no one could take away from him: his poetry,“ she says in an interview with WOMEN AND HOLLYWOOD..

Sudan, the country he comes from, says Hind Meddeb, is a country of poets. „In France, I know people who know poems. But hardly anyone can say them by heart. In Sudan, no matter where you are, people are reciting poems. That‘ s very impressing. You can’t understand the history of Sudan without their poetry.“ It is probably not by coincidence that Hind Meddeb is interested in the literature of Sudan.

“When I heard about Sudan for the first time, I was still a child. It was 1983 and my father was translating the novel Saison de la migration vers le nord from Arabic into French. He wanted to draw the world’s attention to Sudanese literature.“ Her father is the great poet and Tunisian-born Abdelwahab Meddeb. He was one of the most distinguished representatives of French writers of Arab origin until his death in November 2014. Meddeb came from a family of theologians and scribes at Zitûna University. As a poet, essayist and university lecturer, he lived in Paris and was editor of the intercultural journal Dédale. The central concern of the convinced European with Islamic roots was the enlightening potential of Islam. Some of his important writings were published in German translation by Wunderhorn Verlag in Heidelberg.

OUR VOICES AS ONLY WEAPONS

In spring 2019, Hind Meddeb began shooting a new film in Sudan. At the time, she visited the revolutionary sit-in in Khartoum that was the culmination of months of civil society protests. A dream come true to radically change the country. After the military militias attacked the area, burned the tents, erased the paintings and the slogans on the walls, the Sudanese continued their peaceful struggle for freedom despite the violence and the many deaths. Meddeb’s film captures the voices, courage and determination of people across generations, men and women, young and old, who fearlessly lend their voices to the call for freedom and revolution. On her website, she talks about her impressions before, during and after the filming:

“As soon as I arrived in Sudan, I felt home. Being an Arab woman, especially coming from Tunisia where the revolution succeeded 8 years ago, was inspiring for the Sudanese people I met. Everywhere I filmed, I was welcome, and people even came to me to share their stories. Sudanese people felt isolated and asked me to spread the spirit of their revolution.

This film is strongly related to my previous film “PARIS STALINGRAD” and his main character Souleymane who is a young Darfuri teenager escaping war in his country. When the revolution started in Sudan, he wanted to take part of the uprising but it was too early for him to take the risk of heading back to his country. He was very excited I could travel there and bring him back the flavor of this revolution. I travelled filled with the desire of Souleymane and my exile Sudanese friends in Paris. […]

“The day after I came back home, hundreds of people were killed, where I was just filming everyday. I was under shock. I couldn’t believe this amount of violence against peaceful civilians could happen that way, by surprise and in the indifference of the international community. I felt powerless. The only thing I could do is to share my experience of Sudanese revolution, writing, editing, trying to give a voice to those who had no other choice than to stay there, facing bullets and constant insecurity. It’s been a month, the army shut down the Internet to avoid a large coverage of the massacre.

The sit-in was destroyed but it’s still alive in my footage. While I was filming, I was surrounded with beauty. The level of solidarity, courage and determination made people shine from the inside. The sit-in was a city in the city. Microcosm of what a new Sudan would look like, if civilians ruled it. All these years of war and oppression made the people understand they want to live together with their differences. People understood how much racism was just a weapon for the dictatorship, a method to divide people and keep them in a state of oppression.”

Filmographie

2019 · OUR VOICES AS ONLY WEAPONS · documentary, work in progress, Sudan

2019 · PARIS STALINGRAD · documentary, 86’

2018 · KIDS ON THE ROAD · documentary

2018 · STORIE VERE DI PALERMO · travel diary, 22’

2016 · GET ORGANIZED! · documentary, 52’

2015 · TUNISIA CLASH · documentary, 63’

2013 · ELECTRO CHAABI · documentary, 77’

2011 · AU PAYS DE GLISSANT · documentary, 20’

2007 · CASABLANCA, ONE WAY TICKET TO PARADISE · documentary, 44’